ἐν ἀρχῇ ἦν ὁ λόγος — Ιωάννης ο αγαπημένος

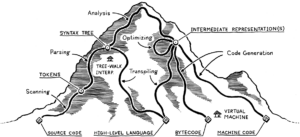

To understand artificial intelligence, you have to start at the beginning—the word. If you look up a word in a dictionary, it is defined by other words, which are in turn defined by even more words. If you keep repeating this process, you end up with a network consisting of all of the words in a language. You can start at any word in that language and plot a course to any other word.

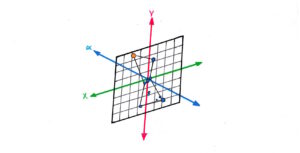

We tend to think of the relationship between words as being vague or fuzzy, but in fact a language is a precise mathematical model in which distances between words can be measured, angles calculated, and relationships derived using trigonometry and calculus.

A word is a singular point in a hyper-dimensional field. The number of dimensions determine the semantic preciseness of the word. Less than a hundred dimensions and the word loses its precision, like a picture out of focus. If you have more than several hundred dimensions, you start to experience diminishing returns. Three hundred dimensions is sufficient for general purposes, but models exist with several thousand dimensions.

You could think of words as being stars in a vast hyper-dimensional universe. It is possible to conceive of time being the fourth dimension and the multiverse as being the fifth, but if you go beyond that it quickly becomes incomprehensible. But there is a way to visualize it that is easily understandable. A three dimensional object can be drawn on a mostly two dimensional piece of paper. A four dimensional being would appear to us as three dimensional with movement.

If you take the dimensions of a word and divide it into three-dimensional slices and superimpose them on top of each other, you have a constellation of dozens of bright stars and hundreds of faint ones. At the center of gravity of this constellation there is a world, where you can look up into the sky and see millions of other stars, both bright and dim.

If you stand on world “Man” and look up and find the star “King” you can teleport to the same place on world “Woman” and in the exact same place in the sky will be the star “Queen.” Similarly, looking at “Queen” from “King” is the exact same relationship as “Woman” from “Man.” There are profound implications and insights that can be derived from this relationship, which we will explore in future posts.

If you break down a word even further into one-dimension points, we now have hundreds or even thousands of sliders or knobs which can be adjusted from off to completely on. This is the definition of a neuron in a neural network. With this paradigm, we can conceive of a word as being a “brain” which takes in a phrase of words and calculates the next word.

Returning to the analogy of a galaxy of stars, a word is a sector of space into which a space ship enters and the gravitational pull of each of the stars redirects and forwards the ship to the next sector in space. The ship starts out with a prompt, and bounces from word to word until it reaches the end of its journal with a complete response.

You see, a language model is a formula, or a condensed mathematical model of the entirety of human knowledge. The coding necessary to build this model is not complex or even particularly sophisticated. It just required the Internet to exist, and a great deal of time, and a lot of money to train it.

Now that we have the model, it’s easy and relatively inexpensive to copy it in high and low definition. But we don’t know what’s in it. We don’t even understand what all the higher dimensions are. This is, in my opinion “the final frontier.” There are insights to be gleaned in linguistics, psychology, and philosophy. A whole new universe exists which is waiting to be discovered and explored!